What Are Dialogue & Deliberation?

Dialogue and deliberation are most useful when people see a discrepancy between what is happening and what they think should be happening in the world or on an issue–yet there is no widespread agreement or shared understanding about what specifically should change. In her book Getting a Grip, NCDD member Frances Moore Lappe asks a powerful question:

“Why are we as societies creating a world that we as individuals abhor?”

NCDD members help people bridge this gap on some of our most challenging public issues.

“Why are we as societies creating a world that we as individuals abhor?”

NCDD members help people bridge this gap on some of our most challenging public issues.

So what are dialogue and deliberation anyway?

|

Dialogue is a process that allows people, usually in small groups, to share their perspectives and experiences with one another about difficult issues we tend to just debate about or avoid entirely. Issues like racial disparities, youth violence and gay marriage.

Dialogue is not about winning an argument or coming to an agreement, but about understanding and learning. Dialogue dispels stereotypes, builds trust and enables people to be open to perspectives that are very different from their own. Dialogue can, and often does, lead to both personal and collaborative action. Deliberation is a closely related process with a different emphasis. Deliberation emphasizes the importance of examining options and trade-offs to make better decisions. Decisions about important public issues like health care and immigration are too often made through the use of power or coercion rather than a sound decision-making process that involves all parties and explores all options. Dialogue and deliberation processes tend to use skilled facilitators and carefully constructed ground rules or agreements to ensure that all participants are heard and are treated as equals. Inclusion is a critical element of both dialogue and deliberation, as a variety of perspectives, backgrounds, and levels of influence enrich the discussion and validate the outcomes. |

Dialogue often lays the groundwork for deliberation. The trust, mutual understanding and relationships that are built during dialogue enable participants to deliberate more effectively, and to make better decisions. For groups that want to move from talk to a decision or action, NCDD recommends starting with dialogue and encouraging deliberation after people have had the chance to share their personal experiences with the issue at hand.

Dialogue and deliberation can serve a variety of purposes, including but not limited to:

(Note: We also have a two pages full of quotes from leaders and up-and-comers in this field answering the questions “What is dialogue?” and “What is deliberation?“)

Dialogue and deliberation can serve a variety of purposes, including but not limited to:

- resolving conflicts and bridge divides

- building understanding and knowledge about complex issues

- generating innovative solutions to problems

- inspiring collective or individual action

- reaching agreement on or recommendations about policy decisions

- building civic capacity, or the ability for communities to solve their own public problems

(Note: We also have a two pages full of quotes from leaders and up-and-comers in this field answering the questions “What is dialogue?” and “What is deliberation?“)

How are these processes really being used?

Citizens, public administrators, teachers, students, organizations, artists and activists are increasingly utilizing dialogue and deliberation to tackle issues and conflicts in new ways. Ways that enable people to share power effectively with each other and with those in power, instead of ways that tend to leave people feeling overpowered and frustrated. Ways that welcome and validate all perspectives on an issue rather than hearing, once again, from only the most vocal and powerful parties.

People are leading D&D programs across the globe in schools, libraries, churches, businesses, community centers, living rooms and online. People are tackling public issues ranging from race relations in their communities to the buildup of nuclear waste or the rapid rate of development in their region, as well as private issues such as conflicts between groups, changes in a workplace, or personal struggles with crises.

D&D are being used more and more as a means to strengthen democracy, in communities, across regions, online and at the national level and even international level. Some programs bring citizens and government decision-makers together as joint problem solvers; some aim to provide decision-makers and voters with the “informed citizen perspective” on an issue; and others aim to equip a group of citizens with the knowledge and will to take action on an issue themselves.

People are leading D&D programs across the globe in schools, libraries, churches, businesses, community centers, living rooms and online. People are tackling public issues ranging from race relations in their communities to the buildup of nuclear waste or the rapid rate of development in their region, as well as private issues such as conflicts between groups, changes in a workplace, or personal struggles with crises.

D&D are being used more and more as a means to strengthen democracy, in communities, across regions, online and at the national level and even international level. Some programs bring citizens and government decision-makers together as joint problem solvers; some aim to provide decision-makers and voters with the “informed citizen perspective” on an issue; and others aim to equip a group of citizens with the knowledge and will to take action on an issue themselves.

So what do D&D actually look like?

|

Techniques range from intimate, small-group dialogues to large televised forums involving hundreds or even thousands of participants. Evolving communication technologies are sometimes integrated into these programs to overcome barriers of scale, geography and time.

The steps in a dialogic or deliberative program vary greatly depending on the purpose of the program, the process used, and the resources that are available. Typical steps of a program that includes both dialogue and deliberation may include: Prep work Get to know the issue, the stakeholders that are affected most, and your participants. Prepare participants for the experience by providing background materials, issue guides that present diverse viewpoints, and details on the process. |

Introductions

Facilitators introduce themselves and the process before proceeding. Participants should feel welcomed and appreciated, and should feel somewhat prepared for what’s ahead of them.

Establish/present ground rules

Also called “agreements,” ground rules are an important part of most D&D processes. Ground rules such as “listen carefully and with respect,” “one person speaks at a time,” “speak for yourself, not for a group,” and “seek to understand rather than persuade” create a safe space for people with very different views and experiences. Adhering to ground rules that foster civility, honesty and respect is what makes D&D so different from adversarial debate and back-and-forth discussion. You may choose to either present a set of ground rules to participants and ask for their changes, additions, and approval, or you may ask participants to come up with agreements that will make them feel safe and productive.

Sharing personal stories and perspectives

Hearing from everyone at the table is a key principle in both dialogue and deliberation. In dialogue, we begin by hearing each participant’s personal stories and perspectives on the issue at hand. We ask “how has this issue played out in your life?” rather than “what do you think should be done about this issue?” or “What’s your take on this issue?” This builds trust in the group, establishes a sense of equality, and enables people to begin seeing the issue from perspectives other than their own. This is especially important when participants have different levels of technical knowledge or professional experience with the issue, or when some participants are not comfortable talking openly about contentious issues.

Exploring a range of views

When a group is fairly like-minded and a wide variety of viewpoints on an issue are just not represented in the group, it is important to make sure the group explores a balanced range of views (this is the big difference between D&D and political activism/advocacy). Some D&D methods meet this ideal by providing participants with carefully developed issue guides that present three or four divergent views on the topic (see National Issues Forums, ChoiceWork Dialogues, or Study Circles). This way, convenors can ensure that participants have the chance to explore and critique all of the primary viewpoints on an issue—even those unpopular with the entire group. Whether the group is exploring their own views or those of others who aren’t in the room, this step prepares them for answering the question “What should we do about this?”

Analysis and reasoned argument

Deliberation is characterized by critical listening, reasoned argumentation, and thoughtful decision-making. David Mathews, President of the Kettering Foundation, says that “Deliberations aren’t just discussions to promote better understanding. They are the way we make the decisions that allow us to act together. People are challenged to face the unpleasant costs and consequences of various options and to ‘work through’ the often volatile emotions that are a part of making public decisions.” The previous steps lay the groundwork for this important step, which often involves reviewing materials that represent a variety of options and viewpoints.

Deciding on action steps or recommendations

Not all dialogue and deliberation programs are designed to lead to collaborative action or to impact decision making. Some programs are designed to educate people about public issues or to build understanding among conflicting groups, for example. If you bring people together for the purpose of action or policy change, it is vital that participants understand how the process they invested time in will or can make an impact—or are supported and guided in making an impact on the issue themselves.

Depending on the process and the program’s purpose, participants may decide to take any number of actions themselves. They may commit to establishing more dialogue groups to discuss and act on the issue at hand. They may establish new personal commitments to change how they handle an issue such as classism in their daily lives. They may make a direct policy recommendation to an elected official or CEO. Or they may start planning how they can self-organize to implement the solutions they came up with.

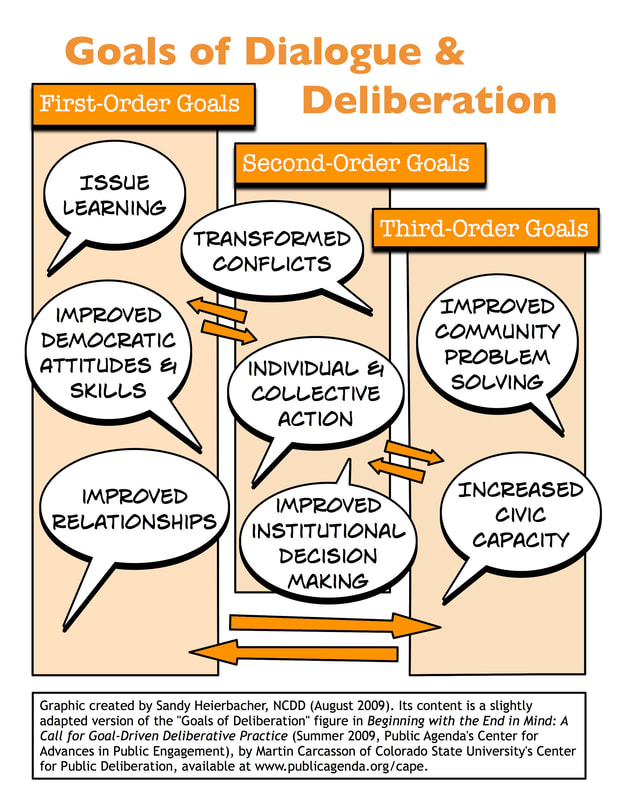

Often, a public deliberation process produces valuable data that becomes one of numerous factors that influence the decisions that need to be made by a policy-maker or other power-holder. In that case, the link from public dialogue and deliberation to a decision may be less direct — but participants can still understand and appreciate this link. They can also be encouraged to value the longer-term impacts of public dialogue and deliberation, like civic capacity-building in their community (see the Goals of D&D image above).

All of the steps above help to ensure that participants are able to create the collective wisdom that is essential for the development of sound, achievable decisions and policies, as well as the common ground and buy-in that is essential for effective, sustainable action to take place.

Facilitators introduce themselves and the process before proceeding. Participants should feel welcomed and appreciated, and should feel somewhat prepared for what’s ahead of them.

Establish/present ground rules

Also called “agreements,” ground rules are an important part of most D&D processes. Ground rules such as “listen carefully and with respect,” “one person speaks at a time,” “speak for yourself, not for a group,” and “seek to understand rather than persuade” create a safe space for people with very different views and experiences. Adhering to ground rules that foster civility, honesty and respect is what makes D&D so different from adversarial debate and back-and-forth discussion. You may choose to either present a set of ground rules to participants and ask for their changes, additions, and approval, or you may ask participants to come up with agreements that will make them feel safe and productive.

Sharing personal stories and perspectives

Hearing from everyone at the table is a key principle in both dialogue and deliberation. In dialogue, we begin by hearing each participant’s personal stories and perspectives on the issue at hand. We ask “how has this issue played out in your life?” rather than “what do you think should be done about this issue?” or “What’s your take on this issue?” This builds trust in the group, establishes a sense of equality, and enables people to begin seeing the issue from perspectives other than their own. This is especially important when participants have different levels of technical knowledge or professional experience with the issue, or when some participants are not comfortable talking openly about contentious issues.

Exploring a range of views

When a group is fairly like-minded and a wide variety of viewpoints on an issue are just not represented in the group, it is important to make sure the group explores a balanced range of views (this is the big difference between D&D and political activism/advocacy). Some D&D methods meet this ideal by providing participants with carefully developed issue guides that present three or four divergent views on the topic (see National Issues Forums, ChoiceWork Dialogues, or Study Circles). This way, convenors can ensure that participants have the chance to explore and critique all of the primary viewpoints on an issue—even those unpopular with the entire group. Whether the group is exploring their own views or those of others who aren’t in the room, this step prepares them for answering the question “What should we do about this?”

Analysis and reasoned argument

Deliberation is characterized by critical listening, reasoned argumentation, and thoughtful decision-making. David Mathews, President of the Kettering Foundation, says that “Deliberations aren’t just discussions to promote better understanding. They are the way we make the decisions that allow us to act together. People are challenged to face the unpleasant costs and consequences of various options and to ‘work through’ the often volatile emotions that are a part of making public decisions.” The previous steps lay the groundwork for this important step, which often involves reviewing materials that represent a variety of options and viewpoints.

Deciding on action steps or recommendations

Not all dialogue and deliberation programs are designed to lead to collaborative action or to impact decision making. Some programs are designed to educate people about public issues or to build understanding among conflicting groups, for example. If you bring people together for the purpose of action or policy change, it is vital that participants understand how the process they invested time in will or can make an impact—or are supported and guided in making an impact on the issue themselves.

Depending on the process and the program’s purpose, participants may decide to take any number of actions themselves. They may commit to establishing more dialogue groups to discuss and act on the issue at hand. They may establish new personal commitments to change how they handle an issue such as classism in their daily lives. They may make a direct policy recommendation to an elected official or CEO. Or they may start planning how they can self-organize to implement the solutions they came up with.

Often, a public deliberation process produces valuable data that becomes one of numerous factors that influence the decisions that need to be made by a policy-maker or other power-holder. In that case, the link from public dialogue and deliberation to a decision may be less direct — but participants can still understand and appreciate this link. They can also be encouraged to value the longer-term impacts of public dialogue and deliberation, like civic capacity-building in their community (see the Goals of D&D image above).

All of the steps above help to ensure that participants are able to create the collective wisdom that is essential for the development of sound, achievable decisions and policies, as well as the common ground and buy-in that is essential for effective, sustainable action to take place.

Want More?

|

If you’re interested in initiating a dialogue and deliberation program in your own community, workplace or school, look over our resource that describes the steps that are typically involved in running a D&D program and lists some how-to tools that provide you with a great starting place based on the type of program you’re planning to run.

We also suggest you download NCDD’s 2010 Resource Guide on Public Engagement and look over our Beginner’s Guide. And see these resources that go into a bit more detail about the basics of dialogue and deliberation: |