|

An annual report that elevates the discussion of our nation’s civic health by measuring a wide variety of civic indicators, America’s Civic Health Index is in an effort to educate Americans about our civic life and to motivate citizens, leaders and policymakers to strengthen it. Among other things, the Civic Health Index measures such factors as engagement in public policy, charitable giving, volunteering, and online participation. Learn more at www.ncoc.org/CHI.

From the National Conference on Citizenship website: Civic Health Index (CHI) is at the center of our work. We think of “civic health” as the way that communities are organized to define and address public problems. Communities with strong indicators of civic health have higher employment rates, stronger schools, better physical health, and more responsive governments. For the past 10 years NCoC, together with the Corporation for National and Community Service and state and community level collaborative networks across the nation, has documented the state of civic life in America in city, state and national Civic Health Index (CHI) reports.

0 Comments

The article, More Than a Seat at the Table: A Resource for Authentic and Equitable Youth Engagement (2016), was written by Rebecca Reyes and Malana Rogers-Bursen, and published by Everyday Democracy. This article explores several challenges when it comes to youth engagement and offers solutions to more effectively engage young people. It is important to engage young people in meaningful ways and for them to be a part of the key decision-making processes. Use this article as a way to gauge if your processes are inclusive of young people and how to improve those processes to better engage youth.

Below is an excerpt of the article from Everyday Democracy, and can find the full article with all the examples of the specific challenges and solutions here. From Everyday Democracy… If you’re working on creating change in your community, it’s important to include all kinds of people in decision-making, including young people. The insight and talents of young people can bring value to any community change effort, yet community groups led by older adults sometimes find it hard to involve younger people, or keep them engaged. We’ve led workshops on youth engagement to help people explore challenges they may face and think about possible solutions. People of all ages and from many sectors contributed their ideas for successfully engaging young people in their efforts. We’ve compiled a number of challenges that you may have encountered in your work or that may come up in the future, along with ways to address these challenges in your group.  Most of the laws that govern public participation in the U.S. are over thirty years old. They do not match the expectations and capacities of citizens today, they pre-date the Internet, and they do not reflect the lessons learned in the last two decades about how citizens and governments can work together. Increasingly, public administrators and public engagement practitioners are hindered by the fact that it’s unclear if many of the best practices in participation are even allowed by the law. Making Public Participation Legal, a 2013 publication of the National Civic League (with support from the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation), presents a valuable set of tools, including a model ordinance, set of policy options, and resource list, to help communities improve public participation. The tools and articles in Making Public Participation Legal were developed over a year by the Working Group on Legal Frameworks for Public Participation — an impressive team convened and guided by Matt Leighninger, formerly of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium (DDC). Here is a wonderful summary by Geoffrey Morton-Haworth of a January 2011 discussion in NCDD’s LinkedIn group on ground rules and best practices in virtual facilitation. The discussion was started by group member Martin Pearson with the subject “Groundrules necessary to make the best of virtual meetings."

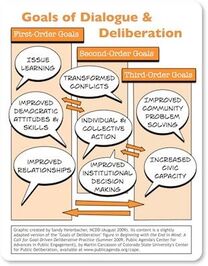

Martin wrote that he was starting to use Skype more for meetings, and asked group members if they have created specific ground rules for their own virtual meetings (like asking people to not to browse the internet while participating in the meeting). The conversation morphed into a rich discussion on best practices for virtual meetings, with over 30 comments shared. Virtual Meetings: Design with the ‘Distracted Participant’ in Mind Geoffrey Morton-Haworth posted on February 03, 2011 03:39 There has been a useful discussion in a LinkedIn group over the last few weeks. The group was the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation (NCDD) and the topic was “ground rules for making the best of virtual meetings”. It is an important topic since more and more of us meet and work together over the internet these days. The drawback with LinkedIn discussions, however good, is that they tend to fade away into hyper-space (I don’t think they are picked up by search engines, maybe this is accidental or maybe it is by design to ensure that such discussions remain relatively private). Therefore what follows is an attempt to distill and record this conversation.  This NCDD report to the Kettering Foundation (pdf) was written by Sandy Heierbacher, NCDD’s Director (2009). Before the October 2008 conference, NCDD embarked on a research project with the Kettering Foundation to learn about how attendees at the 2008 National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation see themselves playing a role in democratic governance. Kettering was also especially interested in two of the five challenge areas taken on at the conference (the Systems Challenge and the Action & Change Challenge). Many NCDD members are quoted in the report, which includes descriptions of a number of their innovative projects and initiatives. Eighty-eight members were surveyed or interviewed as part of this research project, and others contributed through our graphic recording team at the conference, and during the online dialogue we held on the 5 challenge areas at CivicEvolution.org before the conference. The report is 38 pages long, but it’s full of gorgeous photos and graphic recordings from the conference (so it’s shorter than it looks!). The report represents a snapshot of a specific time in this rapidly growing, maturing field of practice. An exciting time, when process leaders and networks in the field are being brought into discussions about federal policy, and when the field is exploring how and whether it fits into a broader “democracy reform” movement. It’s also a time in which we’re seeing clear shifts in approach in the field. Practitioners, organizations and institutions are starting to think in terms of capacity building and find ways to demonstrate perceptible shifts in civic capacity. Practitioners are focusing more on developing ongoing relationships with institutions, decision-makers and other power-holders in the communities they serve. And people are becoming more and more adept at using multiple models, combining elements of different models, and designing unique processes to fit different contexts. You can download the full report here, download a 3-page overview of the report, or learn a bit more about the report below. Feel free to share this report or the overview with others. Summary of the Findings Below is a quick look at the topics that are explored in the report in more depth. What is citizens’ role in democratic governance? When asked how they would describe “the role citizens play in democratic governance,” people responded in five distinct ways. Some took a positive stance, outlining citizens’ critically important role in governance. Others took a pragmatic stance, recognizing that the role of citizens varies depending on a variety of factors. Others responded soberly about the very limited role citizens have in government. Many expressed why they felt the role citizens currently play is far from where it should be. And several outlined what citizens’ role should ideally be in governance. In addition to these five categories of responses, a number of people pointed out that ensuring citizens play a significant role in democratic governance is what our work in dialogue, deliberation and public engagement is all about. Much of the work of those who attended the 2008 NCDD conference focuses on broadening citizens’ role by inviting greater participation in public discussions about critical issues. Types of goals/impacts of dialogue and deliberation What do respondents mean when they refer to the “action and change” that results from dialogue and deliberation efforts? When asked how their work impacts citizens’ role in democratic governance, most respondents mentioned impacts that fall clearly into at least one of the categories in the Goals of Dialogue & Deliberation graphic pictured here. The graphic expands slightly on the Goals of Deliberation figure in an occasional paper published in summer 2009 by Public Agenda. The paper, written by Martin Carcasson, Director of Colorado State University’s Center for Public Deliberation (and a workshop presenter at NCDD 2008), outlines three broad categories of goals for deliberation. In the report, Heierbacher outlines how respondents feel their work falls under each of the sub-categories under the three types of goals, and include direct quotes from dozens of respondents. Carcasson contends in his article that improved community problem solving should be the ultimate goal of deliberative practice. Rather than overly identifying with specific issues or processes (and the squabbles between them) or focusing solely on individual events and projects, Carcasson argues that dialogue and deliberation practitioners should become “known for their passionate focus on democratic problem solving and all that entails.” Here is how Carcasson describes community problem solving: At its best and most effective, community problem solving is a democratic activity that involves the community on multiple levels, ranging from individual action to institutional action at the extremes, but also includes all points in between that involve groups, organizations, non-profits, businesses, etc. It is also deeply linked to the work of John Dewey and his focus on democracy as ‘a way of life’ that requires particularly well-developed skills and habits connected to problem solving and communicating across differences. Many of the 88 respondents mentioned civic capacity building when asked how their work impacts citizens’ role in democratic governance. The action & change challenge More and more people are coming to realize that addressing the major challenges of our time is dependent on our ability to collectively move to a new level of thinking about those challenges, and that dialogic and deliberative processes help people make this leap. Yet we continually struggle with how best to link dialogue and deliberation with action and change, and with the misconception that dialogue and deliberation are “just talk.” For the “Action and Change Challenge,” members explored this question: “How can we strengthen the links between dialogue, deliberation, community action, and policy change?” Eight themes emerged in this challenge area at the 2008 NCDD conference and in dialogues, interviews and surveys with conference attendees:

Survey respondents, interviewees and conference attendees had many other suggestions for this challenge area, and some of those are listed in the report as well. Strengthening the link between public engagement and action and policy change is a challenge that every practitioner struggles with. In this section of the report, a couple of promising frameworks that were presented at the conference are highlighted. Maggie Herzig’s “Virtuous and Vicious Cycles” model is presented, which acknowledges the systemic and cyclical nature of dialogue and deliberation (as opposed to a linear progression of steps or stages). And Philip Thomas’ integral theory of dialogue seeks to reconcile the seemingly incompatible views of dialogue he came across while working on the Handbook on Dialogue published by the United Nations Program on Development and its partners. Thomas interviewed some practitioners who felt, for example, that personal transformation among dialogue participants was a critical outcome to emphasize in the Handbook, while others he interviewed wanted to de-emphasize and even eliminate such concepts from the book and focus primarily on political processes and outcomes. The systems challenge For the “Systems Challenge,” participants explored ways they can make public engagement values and practices integral to government, schools, and other systems, so that methods of involving people, solving problems, and making decisions are used more naturally and efficiently. At the conference, participants focused most on institutionalizing public engagement in governance―an area often referred to by scholars as “embeddedness.” Most of the themes identified as being part of the Action & Change Challenge also overlap with the Systems Challenge in critical ways. Five additional themes emerged in discussions about this challenge area at the conference:

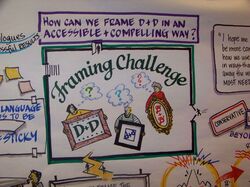

In this section of the report, Heierbacher goes into detail about the outcomes of a two-part workshop at the Austin conference co-led by Adin Rogovin and DeAnna Martin. The workshop brought together method leaders and practitioners in a dynamically facilitated fishbowl conversation to explore how practitioners could weave together their work to enhance democracy. Participants in this workshop discussed how a collaborative, multi-process “demonstration project” could support, fund, advocate for and convene whole system engagement initiatives that involve government officials and demonstrate their legitimacy and value to our society. Susan Schultz, Program Manager of the Center for Public Policy Dispute Resolution at the University of Texas, summed up the Systems Challenge area well with this comment in the survey: It is indeed a challenge to bridge the gap between the concept of having the public involved in public policy decision-making (what is already on paper) and the actuality of having the public influence public decision-making (what realistically happens). I believe that a crucial component in having a meaningful public participation system in place is to make the commitment to that participation part of the organization’s and governmental entity’s culture. Easier said than done, but it starts with clear written policies, commitment to implementing those policies from high level “champions” to field staff (through consistent education and training), and persistent expectations from the public. About the Author The author of this report, Sandy Heierbacher, is the Co-founder of the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation (NCDD) and its conferences. NCDD is a network of organizations, practitioners, and scholars on the leading edge of the fields of intergroup relations, deliberative democracy, conflict resolution, community building and organizational development. Note: Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the Kettering Foundation, its directors, or its officers. NCDD Members’ Views on the Framing Challenge: Results of an Online Dialogue at CivicEvolution6/29/2010 At the 2008 National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation, we focused in on 5 of the most pressing and challenging issues our field is facing – issues that past conference participants agreed are vital for us to address if we are to have the impact we’d like to have in our communities. One of the five challenges we focused on was the “Framing Challenge” — framing this work in an accessible way. Our leader for the Framing Challenge was Jacob Hess.

Six months before the conference, we used the online dialogue and collaborative proposal-writing tool CivicEvolution.org to engage the NCDD community around the 5 challenges. Here is the summary of the discussion about the Framing Challenge, prepared by 2008 conference planning team member Madeleine Van Hecke. This article was written by Sandy Heierbacher at the request of Yes! Magazine (and published on August 21, 2009). Sandy also created two abbreviated versions of this article and a one-page ready-to-print flier for public officials, encouraging NCDD members and others to use the resources freely for blog posts, letters to the editor, etc. during and after the contentious August 2009 town halls on health care. All four of these resources are based on insights and tips shared by NCDD members during this controversial time.

This article was written by Sandy Heierbacher at the request of Yes! Magazine. Sandy also created two abbreviated versions of this article and a one-page ready-to-print flier for public officials, encouraging NCDD members and others to use the resources freely for blog posts, letters to the editor, etc. during and after the contentious August 2009 town halls on health care. All four of these resources are based on insights and tips shared by NCDD members during this controversial time.

The following article is one of a series of articles NCDD created in August 2009 in response to the volatile town hall meetings on healthcare held at the time. NCDD members were encouraged to adapt the articles and submit them as op-eds in their local papers. Go to https://ncdd.org/rc/item/3172 to see the other articles and one-page flyer.

-- Town hall meetings being held on healthcare legislation across the country are exploding with emotion, frustration, and conflict. Citizens are showing up in throngs to speak out about health care as well as dozens of other topics, but it seems the louder voices get, the less people are actually heard. The meetings have become a vivid demonstration of what’s missing in American Democracy. So how can officials hold better open meetings with their constituents? The following article is one of a series of articles NCDD created in August 2009 in response to the volatile town hall meetings on healthcare held at the time. NCDD members were encouraged to adapt the articles and submit them as op-eds in their local papers. Go to https://ncdd.org/rc/item/3172 to see the other articles and one-page flyer.

-- Town hall meetings being held on healthcare legislation across the country are exploding with emotion, frustration, and conflict. Citizens are showing up in throngs to speak out about health care as well as dozens of other topics, but it seems the louder voices get, the less people are actually heard. The meetings have become a vivid demonstration of what’s missing in American Democracy. So how can officials hold better open meetings with their constituents? Dozens of effective public engagement techniques have been developed to enable citizens to have authentic, civil, productive discussions at public meetings—even on highly contentious issues. Techniques like National Issues Forums, Study Circles, 21st Century Town Meetings, Open Space Technology, and World Cafe, to name just a few. When done well, these techniques create the space for real dialogue, so everyone who shows up can tell their story and share their perspective on the topic at hand. Dialogue builds trust and enables people to be open to listening to perspectives that are very different from their own. Deliberation is often key to public engagement work as well, enabling people to discuss the consequences, costs, and trade-offs of various policy options, and to work through the emotions and values inherent in tough public decisions. Given a diverse group, good information, a structured format, and time, citizens can grapple with complicated issues and trade-offs across partisan and other divides. Perhaps most importantly, the legislator hosting the meeting must genuinely be open to learning from what his or her constituents think should be done to address the issue at hand. Here are some guidelines for our political leaders:

These ideas and others posted at www.ncdd.org were developed by members of the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation (NCDD). Though it may not seem like it when we watch clips from recent healthcare town halls, the truth is that people can come together to have a positive impact on national policy—not only in spite of our differences, but because working through those differences allows us to make better decisions. Citizens have higher expectations than ever for a government that is of, by and for the people, and it’s high time for an upgrade in the way we do politics. by Sandy Heierbacher Sandy Heierbacher is the co-founder of the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation (NCDD), a network of groups and professionals who bring together Americans of all stripes to discuss, decide and act together on today’s toughest issues. She recommends the following resources to those interested in engaging the public in healthcare in more meaningful and substantive ways. NCDD Members Directory: www.ncdd.org/directory Find a facilitator or convening organization in your region. NCDD’s Engagement Streams Framework: www.ncdd.org/streams This free resource helps practitioners, community leaders and elected officials decide which public engagement methods are most appropriate for their circumstances and resources. Core Principles for Public Engagement: www.ncdd.org/pep These seven principles were developed collaboratively by leaders in citizen engagement, and have been endorsed by over 50 organizations. The following article is one of a series of articles NCDD created in August 2009 in response to the volatile town hall meetings on healthcare held at the time. NCDD members were encouraged to adapt the articles and submit them as op-eds in their local papers. Go to https://ncdd.org/rc/item/3172 to see the other articles and one-page flyer.

-- Town hall meetings being held on healthcare legislation across the country are exploding with emotion, frustration, and conflict. Citizens are showing up in throngs to speak out about health care as well as dozens of other topics, but it seems the louder voices get, the less people are actually heard. The meetings have become a vivid demonstration of what’s missing in American Democracy. At the 2008 National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation, we focused on 5 challenges identified by participants at our past conferences as being vitally important for our field to address. This is one in a series of five posts featuring the final reports from our “challenge leaders.”

Systems Challenge: Making dialogue and deliberation integral to our systems Most civic experiments in the last decade have been temporary organizing efforts that don’t lead to structured long-term changes in the way citizens and the system interact. How can we make D&D values and practices integral to government, schools, organizations, etc. so that our methods of involving people, solving problems, and making decisions happen more predictably and naturally? Challenge Leaders: Will Friedman, Chief Operating Officer of Public Agenda Matt Leighninger, Executive Director of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium Report on the Systems Challenge: Although no formal report was submitted, Will and Matt identified the following as common themes that emerged in this challenge area:

At the 2008 National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation, we focused on 5 challenges identified by participants at our past conferences as being vitally important for our field to address. This is one in a series of five posts featuring the final reports from our “challenge leaders.”

Evaluation Challenge: Demonstrating that dialogue and deliberation works How can we demonstrate to power-holders (public officials, funders, CEOs, etc.) that D&D really works? Evaluation and measurement is a perennial focus of human performance/change interventions. What evaluation tools and related research do we need to develop? Challenge Leaders: John Gastil, Communications Professor at the University of Washington Janette Hartz-Karp, Professor at Curtin Univ. Sustainability Policy (CUSP) Institute The most poignant reflection of where the field of deliberative democracy stands in relation to evaluation is that despite this being a specific ‘challenge’ area, there was only one session in the NCDD Conference aimed specifically at evaluation – ‘Evaluating Dialogue and Deliberation: What are we Learning?’ by Miriam Wyman, Jacquie Dale and Natasha Manji. This deficit of specific sessions in evaluation at the NCDD Conference offerings is all the more surprising since as learners, practitioners, public and elected officials and researchers, we all grapple with this issue with regular monotony, knowing that it is pivotal to our practice. Suffice to say, this challenge is so daunting that few choose to face it head-on. Wyman et al. made this observation when they quoted the cautionary words of the OECD (from a 2006 report): “There is a striking imbalance between time, money and energy that governments in OECD countries invest in engaging citizens and civil society in public decision-making and the amount of attention they pay to evaluating the effectiveness and impact of such efforts.” The conversations during the Conference appeared to weave into two main streams: the varied reasons people have for doing evaluations and the diverse approaches to evaluation. A. Reasons for Evaluating The first conversation stream was one of convergence or more accurately, several streams proceeding quietly in tandem. This conversation eddied around the reasons different practitioners have for conducting evaluations. These included: “External” reasons oriented toward outside perceptions:

“Internal” reasons more focused on making the process work or the practitioner’s drive for self-critique:

B. How to Evaluate The second conversation stream at the Conference – how we should evaluate – was more divergent, reflecting some of the divides in values and practices between participants. On the one hand there was a loud and clear stream that stated if we want to link citizens’ voices with governance/decision making, we need to use measures that have credibility with policy/decision-makers. Such measures would include instruments such as surveys, interviews and cost benefit analysis that applied quantitative, statistical methods, and to a lesser extent, qualitative analyses, that could claim independence and research rigor. On the other hand, there was another stream that questioned the assumptions underlying these more status quo instruments and their basis in linear thinking. This stream inquired, Are we measuring what matters when we use more conventional tools? For example, did the dialogue and deliberation result in:

From these questions, at least three perspectives emerged:

An ecumenical approach to evaluation may keep peace in the NCDD community, but one of the challenges raised in the Wyman et al. session was the lack of standard indicators for comparability. What good are our evaluation tools if they differ so much from one context to another? How then could we compare the efficacy of different approaches to public involvement? Final Reflections Along with the lack of standard indicators, other barriers to evaluation also persist, as identified in the Wyman et al. session:

Wyman et al commenced their session with the seemingly obvious but often neglected proposition that evaluation plans need to be built into the design of processes. This was demonstrated in their Canadian preventative health care example on the potential pandemic of influenza, where there was a conscious decision to integrate evaluation from the outset. The process they outlined was as follows: Any evaluation should start with early agreement on areas of inquiry. This should be followed by deciding the kinds of information that would support these areas of inquiry, the performance indicators; then the tools most suited; and finally the questions to be asked given the context. A key learning from the pandemic initiative they examined was “In a nutshell, start at the beginning and hang in until well after the end, if there even is an end (because the learning is ideally never ending).” In terms of NCDD, we clearly need to find opportunities to share more D & D evaluation stories to increase our learning, and in so doing, increase the strength and resilience of our dialogue and deliberation community.  At the 2008 National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation, we focused on 5 challenges identified by participants at our past conferences as being vitally important for our field to address. Our leader for the “Framing Challenge” was Jacob Hess, then-Ph.D. Candidate in Clinical-Community Psychology at the University of Illinois. Jacob wrote up an in-depth report on what was discussed at the conference in this challenge area, as well as his own reflections as a social conservative who is committed to dialogue. Download the 2008 Framing Challenge Report (Word doc). Framing Challenge: Framing this work in an accessible way How can we “frame” (write, talk about, and present) D&D in a more accessible and compelling way, so that people of all income levels, educational levels, and political perspectives are drawn to this work? How can we better describe the features and benefits of D&D and equip our members to effectively deliver that message? Addressing this challenge may contribute greatly to other challenges. Challenge Leader: Jacob Hess, then-Ph.D. Candidate in Clinical-Community Psychology at the University of Illinois Here is a taste of Jacob’s thoughtful report: As a social conservative who has found a home in the dialogue community, I was invited to be “point person” for this challenge at the 2008 Austin Conference. The different ways we talk about, portray and frame dialogue can obviously have major differences in whether diverse groups feel comfortable participating in D&D venues (including our coalition). Of course, conservatives are only one example of a group for whom this challenge matters; others who may struggle with our prevailing frameworks include young people, those without the privilege of education, minority ethnic communities, etc. As I learned myself, even progressive people may be “turned off” from a particular framing. After becoming involved in dialogue, I would share what I was learning with classmates and professors during our “diversity seminar.” When hearing about dialogue framed from their white, male, conservatively religious classmate, several of my classmates decided that dialogue must really be a conservative thing—i.e., an attempt to placate, muffle or distract from activism and thereby indirectly reinforce the status quo (a valid concern!). Ultimately, however, in each case I believe these fears are less inherent to dialogue or deliberation itself than to a particular framing of the same. Does dialogue inherently serve either a radical or status quo agenda? Does it require someone to either believe or disbelieve in truth? Does it implicitly cater to one ethnic community or another—one age group above another—one gender or another? I think not. Having said this, little cues in our language and framing may inadvertently communicate otherwise. . . After being identified by the NCDD community (alongside 4 other key challenges), the articulation of this challenge was explored and elaborated in an online discussion of members of NCDD; ultimately, the challenge came to read: “Articulating the importance of this work to those beyond our immediate community (making D&D compelling to people of all income levels, educations levels, political perspectives, etc.) — and helping equip members of the D&D community to talk about this work in an accessible and effective way.” This “challenge #2” is intended to draw our collective attention to how we can make dialogue and deliberation more accessible to more communities—not necessarily by radically altering the practice itself, but my making sure the packaging, the framing and presentation doesn’t inadvertently scare them away. As reframed by Steven Fearing, the “core question” for this challenge becomes: “How can we frame (speak of) this work in a more accessible and compelling way, so that people of income levels, educational levels, and political perspectives are drawn to D&D?” At the 2008 National Conference on Dialogue & Deliberation, we focused on 5 challenges identified by participants at our past conferences as being vitally important for our field to address. This is one in a series of five posts featuring the final reports from our “challenge leaders.”

Inclusion Challenge: Walking our talk in terms of bias and inclusion What are the most critical issues of inclusion and bias right now in the D&D community and how do we address them? What are the most critical issues related to bias, inclusion, and oppression in the world at large and how can we most effectively address these issues through the use of dialogue and deliberation methods? Challenge Leader: Leanne Nurse, Program Analyst for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

Categories

All

|

Follow Us

ABOUT NCDD

NCDD is a community and coalition of individuals and organizations who bring people together to discuss, decide and collaborate on today's toughest issues.

© The National Coalition For Dialogue And Deliberation, Inc. All rights reserved.

© The National Coalition For Dialogue And Deliberation, Inc. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed